We chat to Steph Garratt, winner of the The Floating Circle Prize at the RWA 172 Open…

“…I’m always thinking about the art and imagery that precede me. This piece became my very tongue-in-cheek way of quite literally stitching myself into the broader art historical narrative..”.

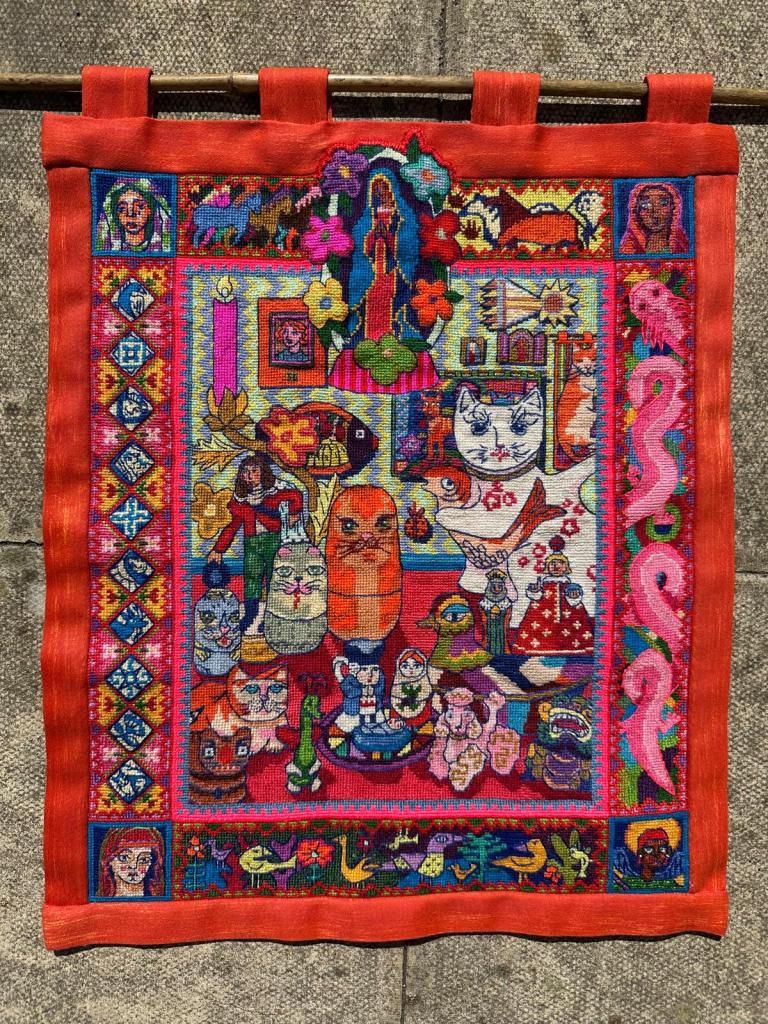

Steph Garratt was the winner of The Floating Circle Prize at the RWA 172 Open for Best Work by an Emerging Artist, for the gloriously original textile work The Bedroom Nativity or The Adoration of the Empty Nesting Doll. We invited Steph to tell us a little more…

Congratulations on winning the Floating Circle Prize! How did it feel to have your work recognised in this way?

Thank you so much to the Friends of the RWA and The Floating Circle for awarding me this prize. I have been lucky enough to have my work selected for the RWA’s open exhibitions several times – which is very gratifying in itself – but to be singled out amongst such incredible, creative company feels very special indeed. I have never been given a prize for my art and never really thought about how it would make me feel, but it suits me fine to see ‘Prize Winner’ next to my name in this exhibition.

The prize is for best work by an ‘emerging artist’. How do you see yourself within that category, and what stage do you feel your practice is at right now?

I never trained formally as an artist, and I don’t make much money from my work – certainly not enough to live on sustainably – so sometimes even calling myself an ‘artist’ feels complicated. I work full-time in a relatively non-creative job and make art on the side. Although it can feel like a hobby at times, my creativity is still the part of me I lead with when I meet new people. When someone asks, ‘So, what do you do?’ I usually say, ‘I’m a textiles artist – but I have a real job too.’ I think that’s something many artists today can relate to, working to pay the bills, then pouring whatever time and energy remains into making art.

I’d describe myself as an emerging, early-career artist – but even that label feels a bit loaded. To be an ‘emerging artist’ suggests that discovery is just around the corner, that I might soon leave my 9–5 behind to pursue art full time. But I don’t think that’s what I want. Of course, I love when my work is recognised, and it’s always exciting to make money from it, but I don’t want to depend on that income. I like keeping my creative life separate from the part of me that goes to work and pays the bills – it’s my escape, my space for wellbeing and honestly, I worry that if I ‘emerged’ too far, I might lose that balance.

Can you tell us about the winning work, The Bedroom Nativity or The Adoration of the Empty Nesting Doll? What inspired it, and how did it develop?

I began this piece during a solo holiday in Lisbon back in January. At the time, I had no clear vision for what it would become – I just knew I felt deeply inspired by the city, especially the ceramic tiles that seemed to adorn every surface. I started by stitching miniature versions of my favourite tiles, which now line the left-hand border of the piece. As I wandered through Lisbon’s churches and museums – my favourite places to explore when travelling – I found myself captivated by the richly detailed wooden Nativity scenes, or cribs, that appeared everywhere. These elaborate 3D dioramas featured not just the traditional holy family, but an entire world around them: villagers, animals, angels, plants, buildings, even mountains. Each scene was a universe in itself, intricate and overflowing with character.

Though I’m not religious, I’ve always felt drawn to sacred imagery and ritual objects. At home, I’ve created my own kind of shrine, a collection of small figurines – animals, people, odd little characters – that I’ve gathered over the years from different places. I call them my ‘little guys.’ They lived in my bedroom, and each one carries a weight of memory, nostalgia, and personal meaning. In many ways, they are my ritual objects. When I returned from Lisbon, I decided to stage my own version of a Nativity using these ‘little guys.’ I arranged them into a tableau, photographed the scene, then sketched it onto fabric and began embroidering each figure, one by one. The whole piece took around five months to complete, with stitches added nearly every day.

At the centre is my unconventional holy family: a tiny Toby Jug as Joseph, the smallest nesting doll from a set as Mary, and a miniature ceramic baby Jesus I found years ago at a flea market in France. Surrounding them, I filled the borders with imagery that’s entirely personal and joyfully eclectic. The right border features a long, twisting pink axolotl – a tribute to my pet axolotl, Grayson, who shared a tank with his brother Billy in my bedroom. The bottom border is filled with Paul Klee-inspired birds, while the top border blends horses drawn from the Bayeux Tapestry on the left with those inspired by prehistoric cave paintings on the right. There’s no logic to the imagery – it’s simply a collection of things I find beautiful, strange, or meaningful. Together, they form a stitched world that feels both sacred and entirely my own.

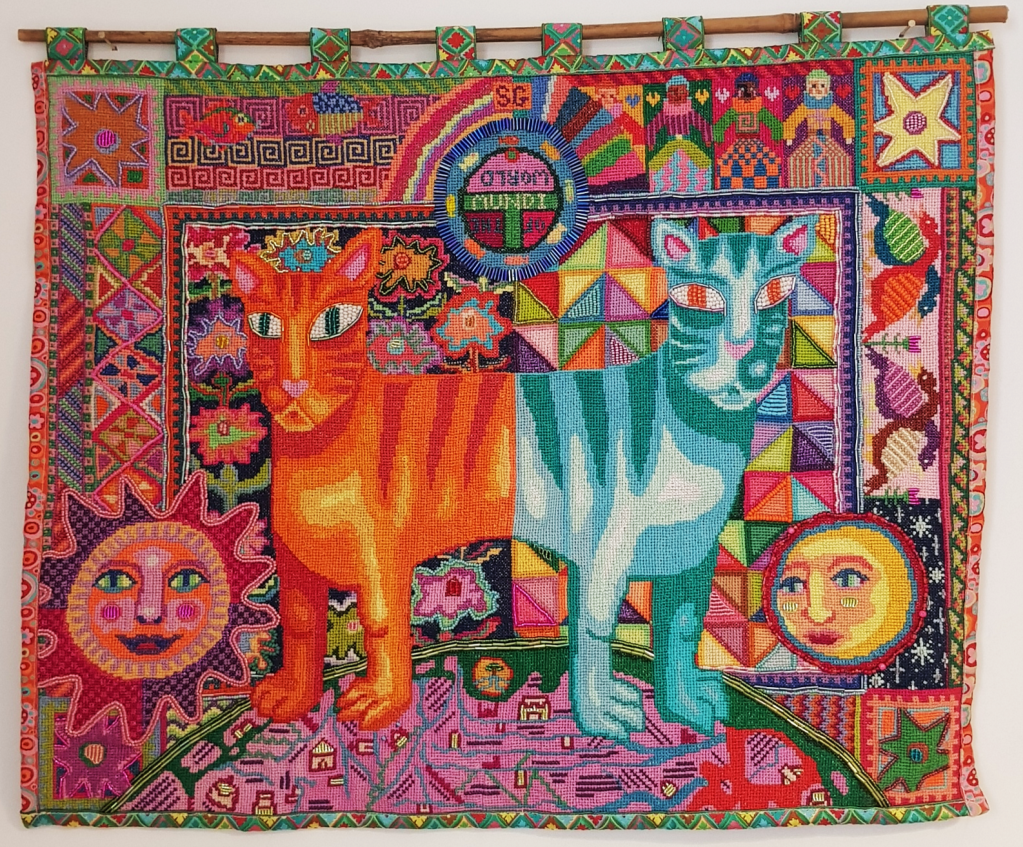

Your embroidery is full of humour and curious details – cats, toys, figurines, even a nod to your earlier piece Of The World (Mundi). Do you consciously set out to tell stories through these objects, or do they emerge more intuitively?

I recently moved into a new home, leaving behind my old, much-loved bedroom – which inspired the title of this artwork. I didn’t realise when I was creating it, but now, in this new space, the embroidery has taken on a deeper meaning. It has become a kind of tribute to that room, that old house with all the memories and milestones that unfolded within its walls. The good: endless hours making art, bringing home my beloved cat Ginge, spending time with friends, falling in love, and the bad: periods of depression, panic attacks, arguments with family and friends, and times when I felt completely disconnected from my creativity. I hadn’t set out to commemorate that chapter of my life – but looking at this piece now, I realise that’s exactly what I’ve done. It holds the fullness of that time – its joy, its pain, its whimsy – and I’m grateful to have captured it, even without meaning to.

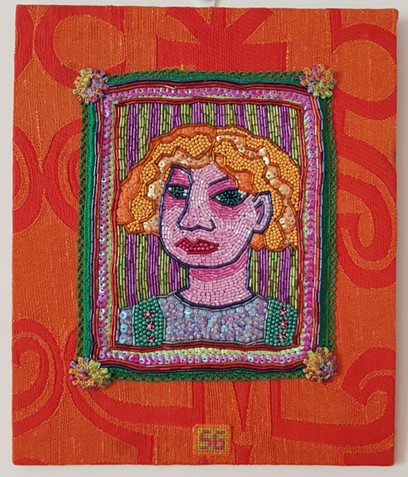

In response to your question, I wouldn’t say I consciously tell stories through my art, but I do enjoy reimagining pre-existing stories in my own way. This piece, for example, is a reinterpretation of a biblical story, and I’ve created other works inspired by various other religious and folkloric narratives. I re-work these timeless, legacy-laden tales into visual stories that feel playful, intimate, and personal. That’s why I included references to some of my other pieces within this work. Of The World (Mundi) – which you noticed – is the piece I sold at last year’s annual open, marking a huge milestone for me as my biggest sale to date. I’ve also woven in an earlier self-portrait and an embroidery of my cat, which featured in the 169 Annual Open Exhibition. Alongside these more personal works, I’ve incorporated depictions of painted birds by Paul Klee and embroidered horses from the Bayeux Tapestry. Having studied Art History and then Medieval Studies, I’m always thinking about the art and imagery that precede me. This piece became my very tongue-in-cheek way of quite literally stitching myself into the broader art historical narrative.

Why embroidery? What draws you to textile art as your medium of choice?

I’ve always loved sewing, and textiles was one of my favourite subjects at school, but it didn’t truly become my chosen medium until a few years ago. I spent an incredible year (2022-23) volunteering at Studio Upstairs, an art therapy charity based on Spike Island that provides long-term mental health support for some of Bristol’s most vulnerable people. It’s an incredible place, filled with compassionate therapists and inspiring members, many of whom I got to know well during my time there. My role was to create art within the studio, share my work with the members, and support them with their own creative projects – or encourage them to explore new ones. When I first started, I found it difficult to make art in front of others as I was used to showing my work only when it was finished. But that soon changed.

One day, I began sewing using wool embroidered into hessian and a member noticed my tapestry loop and asked about it. I offered to show them, and we sat together, mostly in silence, stitching side by side. The following week, they returned with their own loop, eager to show me what they’d made at home. They told me that holding onto the loop made them feel safe and in control – that grasping something tangible and keeping it close helped ground them. I realised that’s exactly how embroidery made me feel too. I’ve struggled with anxiety for a long time and was experiencing intense dissociation at that point in my life, but with the loop in my hands, feeling the textures of the hessian and wool, I found myself reconnecting with my body and the physical world around me. It grounded me and gave me a sense of control again. From that moment, I was hooked, and I’ve worked almost exclusively in textiles ever since.

Now, textiles have become a daily practice. I carry my current project wherever I go – sewing in the pub, on the bus, in the park – constantly making, stitching, or knitting. I have come to really appreciate the time that it takes to make something in textiles, it is a slow process, but one that feels reliable and constant for me. The act of making has become more important to me than actually finishing something. When I complete one piece, I immediately start another – keeping my hands busy and giving my mind space to unravel.

The RWA’s recent Soft Power exhibition highlighted how textiles can carry powerful personal and political narratives. Do you see your own work in conversation with that tradition?

Soft Power was a wonderful and deeply significant exhibition – one I had been anticipating for a long time and was fortunate enough to attend the private view of. As someone who works primarily with textiles, it can often feel challenging to justify my practice within a fine art context. Historically, mediums like painting and sculpture have been elevated above others, while textiles have been relegated to the realm of ‘craft,’ or, until relatively recently, dismissed as merely ‘women’s work.’ It was therefore incredibly affirming to see a major exhibition – hosted within Bristol’s oldest art gallery – that celebrated the work of women and non-binary artists who have chosen textiles as their medium.

Across the world, textile practices have long provided a means for women to express themselves, collaborate, and find autonomy within societies and circumstances that restrict their freedoms. One of the most moving moments for me was encountering the embroideries by artist Amneh Shaikh-Farooqui, created in collaboration with Afghan refugee women. These works speak powerfully of silencing, displacement, and loss, yet they also embody resilience, solidarity, and spirit – emotions now eternalised in stitch and presented to the world as fine art.

I like to think of my own work as part of this ongoing tradition. My practice, too, holds a kind of ‘soft power,’ even if it exists only for me. Each time I learn a new technique, spend hours in quiet concentration, or hang a finished piece on the wall, I’m reminded of the countless people, cultures, and communities who have perfected their craft over centuries – slowly, deliberately, and meaningfully. In those moments, I feel an unexpected but profound sense of connection to them, a thread linking my work to theirs across time and place.

Which artists or makers (textile or otherwise) have influenced or inspired you?

I take a lot of inspiration from folk and outsider artists like Madge Gill and Maria Prymachenko, as well as different folk textile traditions from around the world – Haitian Drapo, or Panamanian Molas for example. I am also a huge advocate of arts organisations that support artists with disabilities, mental ill health or other barriers to making such as Arthouse Unlimited, IntoArt and Outside In and am currently enjoying the work of Michelle Roberts and Jordan Moody. I also take a lot of inspiration from medieval ritual objects, manuscripts and maps, as well as more modern artworks – one of my favourite paintings is a work called Fish Magic by Paul Klee, currently held in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which I hope to be able to see it in person one day.

As someone who has worked at the RWA, how important is the gallery for you as an artist?

I worked at the RWA for two years, from 2022-24, spending most of my time behind the front desk, but also moving into their marketing department after a while. It was fantastic to be so closely involved with the exhibitions taking place, with the art on display and with the creative community that surrounds and supports the gallery. I was able to work with some truly wonderful people, many of whom were creatives, and artists in their own right. This is something that you will find at lots of art galleries and cultural institutions, that the people who keep the place ticking over, have their own creative practices and are trying to carve out their own space within the creative landscape.

I had the wonderful opportunity to project manage a staff exhibition, Also Artists, which ran for several months toward the end of 2023. Together with my fantastic colleagues, we curated a small but meaningful show that highlighted the personal projects of RWA day staff, drawing school tutors, and project partners. I’m incredibly proud of that exhibition and hope that more galleries continue to recognise and celebrate the creative talents of their own teams in similar ways.

Since leaving the RWA, I’ve stayed in touch with many of the artists I met during my time there. They’ve become friends, mentors, and ongoing sources of inspiration, and I feel deeply grateful to have been part of such a talented and generous community. Receiving this award from the Friends of the RWA feels especially meaningful, as I came to know many of them while working at the gallery. It truly feels like a full-circle moment.

What are you working on now, or what’s next for you?

Having recently moved into a new flat, I’ve found that most of my creative energy has been channelled into decorating. So far, I’ve knitted a cushion cover, made curtains for both the bedroom and living room, and my next project is to paint a few lampshades. I have some ideas forming for my next larger piece, but I don’t quite feel ready to dive in until I’ve finished creating my new space with my partner. I did, however, acquire a pair of wonderful antique lion statues recently and I have a feeling they’ll play a starring role in whatever I create next.

Finally, what advice would you give to other emerging artists thinking about submitting to the Open?

Submitting work to an open call can be a daunting experience. Rejection after rejection can leave you feeling disheartened, and the financial cost of entry can be a significant barrier. For many emerging artists, especially those who don’t yet earn much from their work (like me), paying to enter an exhibition you might not even be selected for can be a real deterrent. It prevents many talented young artists from sharing their work and gaining visibility.

That said, submission fees are often a necessary reality for most galleries. Institutions like the RWA are charities that rely on public income to keep their doors open and to fund the incredible outreach programmes they run. When I enter my work into an RWA open call, I always hope to be selected – and I’ve been fortunate a few times – but even when I’m not, I know exactly where my money goes. It supports community outreach and education initiatives, including projects for families with children with SEN+D, refugee women’s groups, and people living with dementia, just to name a few. These vital programmes simply wouldn’t exist without the funding generated through open call submissions, and it feels good to know that, in some small way, I’ve contributed to them over the years.

And when your work is chosen, it’s an extraordinary bonus – a moment of recognition that reminds you why you keep creating and putting yourself out there. That’s certainly how it feels to me.

Follow Steph on Instagram @stephg.art.

The RWA 172 Open continues until 28 December 2025.