“Show your soul to the world.” Artist Tony Eastman’s work has taken him around the world. Here he shares his stories of working without a studio, how engineering shows up in his work and a long-term attachment to the culture of people in Japan.

by Jamillah Knowles

A prolific maker of sculptures and mixed media works, Tony Eastman has been working on collections of chairs, landscapes, small buildings and collage for decades. His initial interest in the arts was more of a resistance than an encouraged career option. Sitting together in his house in Bristol he talks about passionate but difficult beginnings.

“I wanted to be an artist but my father said, do you want to go into the army or work in the dockyard? I reluctantly chose to do an engineering apprenticeship at the dockyard, five years long and five days a week, 7am to 7pm..

Tony was determined to continue a creative path, even after the long hours. “I took two hours of evening classes at the end of each day. I used to hide away inside aircraft carriers and paint.” The morning he had his indentures in hand, he enrolled on an art foundation course. “That afternoon, I was life drawing,” he says.

A three-year sculpture degree course at Bath Academy of Art followed and on finishing, a stint at teaching metal work, landscape gardening and factory work filled the time before Tony was offered part-time lecturing work at Salford University and Cheshire Art college. This part-time work gave him the time to develop his own practice.

Tony’s interest in Japan and his experience as a landscape gardener led him to create work in the environment. Travel furthered his talent. He was awarded Arts Council grants to study native architecture and earth buildings in France and the U.S.. The British Council award led him to create an environmental sculpture project in Japan.

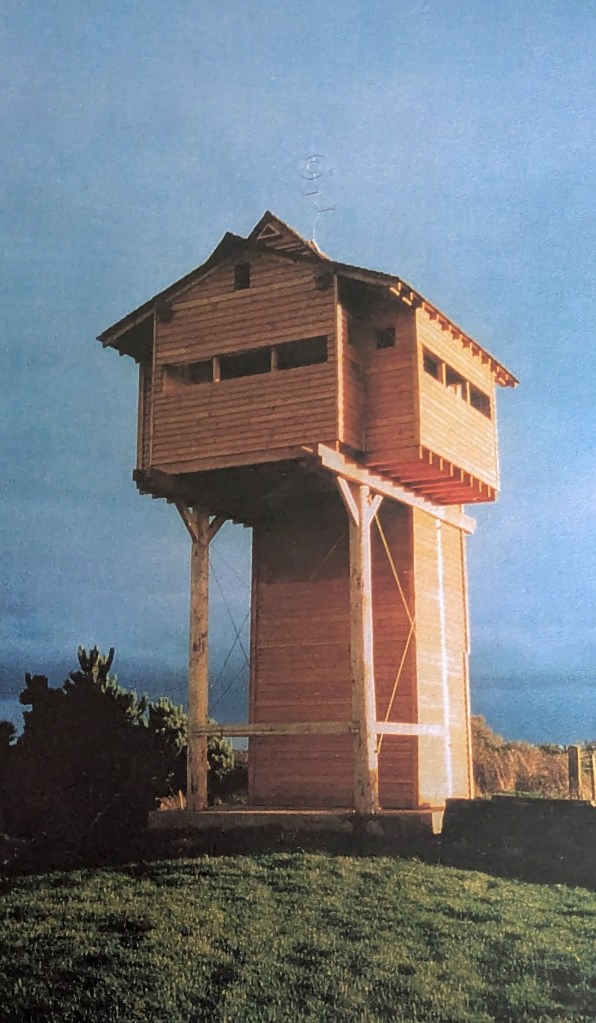

A commission with architect Wilf Burton to design a Japanese-inspired bird hide in Somerset required his research and he continued to successfully pursue exhibitions across the UK and abroad. During this period, Tony also ran a unique creative project for young unemployed people, working in the environment and with communities.

Influences abroad

Travel has had a deep impact on Tony and his work. He travelled to Japan, across Europe to Moscow and through Siberia – and it changed his thinking about creativity. “The zen gardens absolutely blew me away,” he says.

Tony’s observations of Japanese Noh theatre traditions led to making a mask of his own. “They wear masks and then use their hands to tell the stories and allude to landscapes. I was so inspired by this long tradition in theater that I made my own articulated mask from perspex. It was interesting working through the prototypes and to make a mask that changes what the traditional masks mean, by allowing audiences to see through the material and recognise their faces.”

He has also made shoes based on traditional Japanese geta. Originally these shoes are designed to raise the wearer off the ground and protect the hems of clothing. Often they are carved out of a single block of wood and can have raised heels. In a playful translation, Tony created shoes that are raised at the back for one foot and the front on the other and filled with items that rattle if the wearer is able to walk in them. The red-lacquered outcome is striking and leads the viewer to consider our methods of walking and ease of modern footwear.

“In Japan, I learned to pay attention to small things,” Tony says. “There’s a few things I have collected that have tiny wooden bells, you pay attention to the fact they put something on an object that you might not see normally. It might be a chopstick holder for the table or a wooden spoon for measuring tea. They are attentive and it’s a very focused culture.”

The reality of making art

While Tony has enjoyed success in different parts of the world, he acknowledges the lessons of working as an artist and the risks and the barriers that we all face. Although he has worked from many studios over time, he now works from home and has taken inspiration from past locations of work.

“For a few years I had a studio in Park Street,” he says. “In that time, I didn’t take any machinery with me, not even a drill. I kept a diary for 55 years and I would go into the studio, I would note things in the street that I saw and I would do a drawing bedside. For ten years I worked almost exclusively on brown paper and with some Meccano and laser cut steel.”

“I now work small because I work in the house. I’ve been very lucky to have some very big commissions, but those are finite. Now there’s a quest to make things that are very satisfying but don’t take up too much space. I find that people like me who have retired have a house full of work.”

After so many years as a working artist, it’s not surprising that Tony has lessons he is willing to share with others, especially those who are just starting in their career. “Every now and again you get something, that though no fault of your own goes wrong. You have to take it on the chin, pick up your bag and get some more work. Also learn that you will get a lot of rejection and it’s not you. Try and try again, show your soul to the world.”

Tony acknowledges the steady support of his wife Glen throughout his career. “Sometimes there’s plenty of work and other times it stops on a precipice and I wonder if I have to go jobbing again. My wife worked for years while I made my stuff. It can be a tricky balance.” He notes that the precarious nature of making art in order to make a living is linked to cultural awareness in society. “A lack of work is not even acknowledged unless you are a commercial artist,” he says. “This is a sign of how we value art in our society. In Japan if you are an artist for some time, you are a living treasure – whether you are a candle maker or a carver or a painter. I think that’s wonderful.”

While making art is not an easy way to work, Tony keeps going and admires the same resilience in others, “I am enchanted by the fact that there are people all over the world who found a very positive method of self expression that’s very personal to them. Having an imagination is one of the greatest gifts. It propels you through difficult times. If it was easy, it wouldn’t be worth doing.”

See more of Tony’s work on Instagram @tonyeastman.artist.

Jamillah Knowles is a writer, artist, AI specialist and RWA Friend. You can read a Floating Circle Meet the Artist Q&A with her here.